Surge in Global Electricity Demand

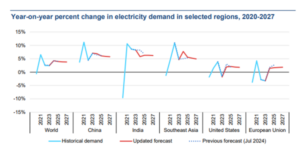

Global electricity consumption is entering a new phase of acceleration. Between 2025 and 2027, demand will grow by around 4% each year, following a 4.3% rise in 2024.

This means the world will add about 3,500 TWh of electricity use in only three years — equivalent to adding Japan’s total annual demand every year.

Behind this surge are several global forces: growing industrial activity, the rising need for air conditioning, the electrification of transport and buildings, and the worldwide boom in data centres.

As the International Energy Agency (IEA) notes, the world is “raising the curtain on a new Age of Electricity” — where power underpins both economic and digital transformation.  Global power demand is set to grow 4% annually through 2027, led by Asia

Global power demand is set to grow 4% annually through 2027, led by Asia

Asia Leads the Global Energy Expansion

Emerging economies, led by Asia, are driving this new electricity age. By 2027, the region will account for 85% of global demand growth, with China alone responsible for more than half.

China’s electricity consumption rose by 7% in 2024 and is forecast to keep growing around 6% annually. India and Southeast Asia are also accelerating, fuelled by rapid industrialisation and higher residential usage.

For example, India’s demand is expected to grow 6.3% per year during 2025–2027, outpacing its previous decade’s average. Meanwhile, Africa’s progress remains uneven — nearly 600 million people in sub-Saharan Africa still lack electricity access, showing the deep global energy divide.

Industrial Sector’s Impact

Asia’s industrial sector is a key force behind its electricity surge. In China, industries consume nearly 60% of all electricity — compared to just 32% in OECD countries.

From 2022 to 2024, almost half of China’s power demand growth came from manufacturing, especially solar PV, batteries, and EV production. These “new energy” industries alone used over 300 TWh of electricity in 2024 — as much as Italy’s total annual use.

This shift marks the electrification of industry itself. Sectors like chemicals and refining are replacing fossil-fuel heating with electric heating and industrial heat pumps. It reflects a deeper structural change in how energy is produced and consumed.

In advanced economies, the story differs. After a decade of stagnation, electricity use is rebounding. The U.S., EU, Japan, Korea, and Australia are all seeing renewed growth, driven by EV charging, heat pumps, and expanding data centres.

Shifting Supply: Renewables and Emissions

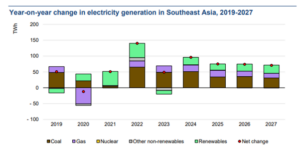

Low-carbon power is expanding faster than ever. Renewables — led by solar, wind, and hydropower — together with nuclear energy, will meet 95% of new global demand through 2027.

By 2025, renewables will supply over one-third of global electricity, overtaking coal for the first time in a century. Solar generation alone reached 2,000 TWh in 2024. Another 600 TWh will be added annually through 2027 — equal to South Korea’s total yearly demand.

At the same time, coal’s share is set to fall below 33%, while wind and nuclear continue to expand. This clean energy surge is already flattening global emissions. After a 1% increase in 2024, power-sector CO₂ emissions are expected to plateau by 2027 as renewables offset growing demand.

Coal remains dominant, but renewables are growing rapidly across Southeast Asia

Vietnam’s Electricity Outlook

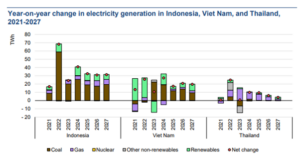

Vietnam stands out as one of Asia’s fastest-evolving electricity markets. Consumption has grown eightfold since 2002, reaching over 240 TWh in 2022, driven by industrialisation and manufacturing expansion.

To meet this rising demand, Vietnam has diversified its power generation across coal, hydropower, gas, and solar PV — which grew rapidly to make Vietnam one of Southeast Asia’s top solar markets.

As of 2022, coal accounted for 41% of generation, followed by hydropower (35%), gas (11%), and solar (~10%).

Vietnam’s power mix is shifting, with coal surpassing 50% share by 2027

Vietnam’s Power Development Plan VIII (PDP8) outlines an ambitious roadmap toward 2030 and 2050. Electricity demand will double by 2030 and grow fivefold by 2050, reaching nearly 1,200 TWh.

Coal generation will peak in the mid-2020s, while gas and renewables take centre stage. By 2030, non-hydro renewables are targeted to reach 21% of total capacity, up from 9.4%. Meanwhile, coal’s share will drop from 52% to 43%.

By 2045–2050, wind and solar will dominate Vietnam’s power mix, alongside hydropower, gas, and emerging low-carbon fuels such as biomass, hydrogen, and ammonia.

To enable this shift, annual investments of about $30 billion will be needed for new generation and grid upgrades. Under PDP8, power-sector CO₂ emissions are expected to peak at 250 million tonnes in 2030 and decline to 30 million tonnes by 2050 — aligning with Vietnam’s net-zero goal.

Need for Flexibility and Reliability

As renewables grow, grid flexibility becomes the next major challenge for energy security. Countries like Vietnam must prepare for variable generation, energy storage needs, and price volatility.

The IEA stresses the importance of modern market designs, adaptive tariffs, and investments in storage and interconnections to stabilise renewable-heavy systems.

For Vietnam, maintaining reliability will require:

- Large-scale battery and storage deployment

- Modernised grid infrastructure

- Smart demand-side management

- Flexible natural gas as transitional support

📚 Sources

International Energy Agency (IEA) & Viet Nam Ministry of Industry and Trade (MOIT).

Achieving a Net Zero Electricity Sector in Viet Nam: Technical Report.

Paris: IEA, 2024.

🔗https://www.iea.org/reports/achieving-a-net-zero-electricity-sector-in-viet-nam

International Energy Agency (IEA).

Electricity 2025: Analysis and Forecast to 2027. Paris: IEA, 2025.